Wild Words: Gaelic Place-names in Callander

Dr Ross Crawford on how Gaelic place-names, natural and cultural heritage, and folklore instils 'belonging' in the landscape.

Dr Ross Crawford, the Cultural Heritage Adviser for 'Callander's Landscape' project, shares what Gaelic place-names can tell us about the natural and cultural heritage of an area and how Gaelic folklore, poetry and, song instils a sense of “belonging” in the landscape.

Dr Ross Crawford, the Cultural Heritage Adviser for 'Callander's Landscape' project, shares what Gaelic place-names can tell us about the natural and cultural heritage of an area and how Gaelic folklore, poetry and, song instils a sense of “belonging” in the landscape.

---

The Intangible Made Tangible? The Cultural Heritage of Gaelic Place-names in Callander

Where would we be without place-names? We mostly take them for granted, but they have a crucial function in our everyday lives. Just imagine trying to travel from Aberdeen to Ayr, or Tokyo to Tighnabruaich, without invoking a single place-name! More than just their pure utility, place-names also provide a rich insight into the landscape around us – how it has changed over time and how it was understood by our predecessors.

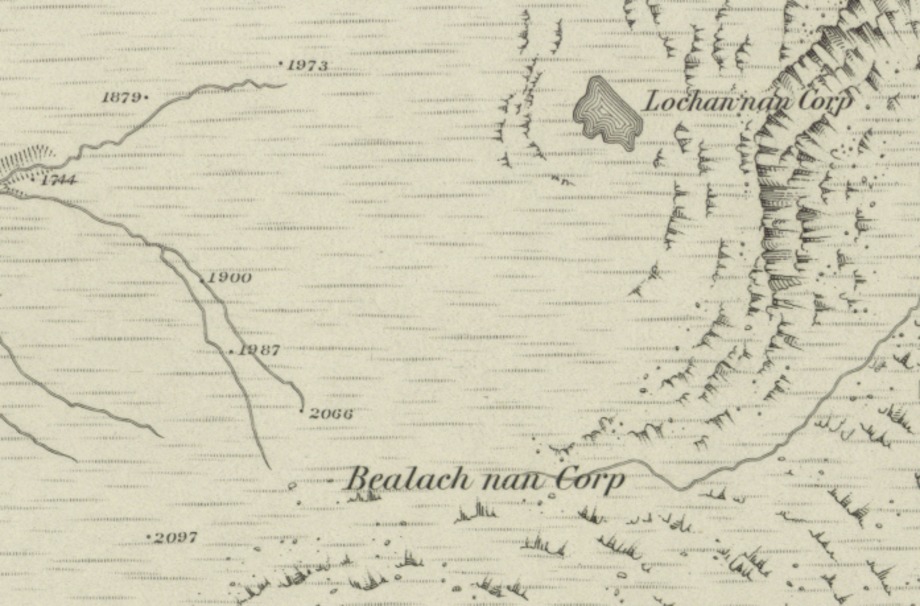

As part of Callander’s Landscape, a partnership project funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, we aim to highlight and celebrate the rich Gaelic heritage of Callander (or Calasraid in Gaelic). Place-names are an obvious place to start: pick up an Ordnance Survey map of the Callander area and you’ll see that Gaelic place-names dominate the grid. Most of the famous landscape features in Callander were named by Gaelic speakers – Ben Ledi, Callander Crags, Bochastle, Loch Venachar, and many more.

Place-names can be used as a window through which we can view the lives of people of the past, especially from the pre-industrial period when Gaelic was the main language in the Callander area. We can vividly imagine a blacksmith working the bellows along the riverside (Eas Gobhain – Smiddy’s Water), the priest giving his morning service (Maol an t-Sagairt – Knoll of the Priest), and hunters assembling for the morning’s pursuit (Creag na Comh-sheilg – Crag of the Joint Hunting).

On many Highland hillsides, you will come across àirigh place-names, which refer to shielings, the mountain pastures where people would spend the summer herding cattle. Look closer and you will often spot another nearby place-name, similar to Bealach na h-Imrich (Pass of the Flitting) near Callander, which plots the exact route people would take to reach the shielings from the township. Other place-names can help us to walk in the footsteps of our ancestors, although some have a more sombre origin. On the northern slopes of Ben Ledi we can still find Bealach nan Corp (Pass of the Bodies), which indicates a corpse path, a route taken by funeral parties to reach consecrated ground. In this instance, it would seem to link the people of Glen Finglas with St Bride’s Chapel on Loch Lubnaig and the churchyards at Kilmahog and Callander.

Many of the place-names discussed so far have clear meanings, but some can be obscure, providing only a tantalising hint of a story once told. In Leny Woods, there are two place-names with military connotations that may be related: Meall nan Saighdear (Hill of the Soldiers) and Bealach nam Biodag (Pass of the Dirks). Could these have anything to do with the Jacobite backsword, held by NTS Culloden, originally discovered in the Garbh Uisge just down the road? Or did locals name the hill after William Roy and his military cartographers, who surveyed this area around 1747? Folklore and place-names are often intimately bound together. Along the northern banks of Loch Venachar, you can find Coille a’ Bhròin (Woods of Sorrow) which tradition-bearers say marks the spot where an each-uisge (water horse or kelpie) swept away a group of school children around 250 years ago.

There can be no doubt that place-names can provide an insight into the past, but we also must be mindful that Gaelic is a living language still spoken in Scotland, including Callander and its environs. As shown by the work of Ruairidh MacIlleathain, John Murray and others, place-names can act as a gateway to wider language learning, as finding out more about the landscape can be hugely addictive! There are many online resources to help you get started, including Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba’s database and Am Faclair Beag, a comprehensive Scottish Gaelic dictionary. If you choose to engage with Gaelic place-names, you will be rewarded with a heightened intimacy with our landscape, making this “intangible heritage” come within touching distance.

Find out more about Callander's Landscape Project

Image credit: reproduced with the permissions of the National Library of Scotland

---

Celebrate our Wild Words month with this special offer: 25% off for your first year of John Muir Trust membership* if you join us during October 2019. Use the promo code: WILDWORDS (*Ts & Cs apply).