Wild and Well: Muigh san Aonach/ Out in the Mountains

Photographic and sound artist, Judith Parrott, explores the relevance of belonging for personal and environmental wellbeing in traditional Gaelic culture.

For 19 years I have worked as a photographic and sound artist, exploring the relevance of belonging for personal and environmental wellbeing, starting conversations with interesting people in fascinating places. Then, with isolation brought about by the pandemic, life became less mobile, more embedded in the local environment, and engagement with the landscape became key to wellbeing.

For 19 years I have worked as a photographic and sound artist, exploring the relevance of belonging for personal and environmental wellbeing, starting conversations with interesting people in fascinating places. Then, with isolation brought about by the pandemic, life became less mobile, more embedded in the local environment, and engagement with the landscape became key to wellbeing.

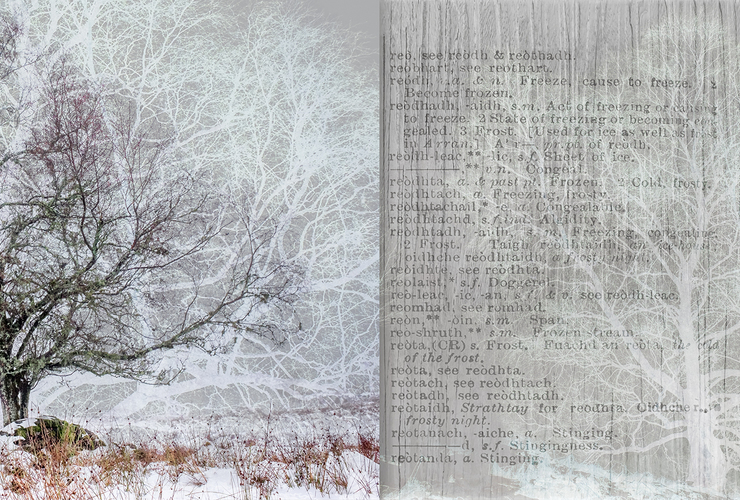

In traditional Gaelic culture such engagement is evidenced in the 18 letters of the Gaelic alphabet, each represented by the name of a tree or shrub. John Burnside writes in a Guardian review of Robert MacFarlane’s book Landmarks: "Indigenous people have always known that language and the land are continuous".

In the early 1900’s, Dwelly’s Gaelic Dictionary finds 73 translations for ‘ocean wave’, each describing a variation in season and formation. None of this can be expressed in one word in English. Nevertheless, seasons continue to shape landscape, and together they have a profound affect on contemporary everyday life and on how we feel.

Does language affect our perception of the world?

In my research for the recent exhibition, Rionnach Maoim [1] , I asked the question: Does language affect our perception of the world? I came across this in Robert MacFarlane’s article [2]:

"… Under pressure, Oxford University Press revealed a list of the entries it no longer felt to be relevant to a modern-day childhood. The deletions (from the Oxford Junior Dictionary) included acorn, adder, ash, beech, bluebell, buttercup, catkin, conker, cowslip, cygnet, dandelion, fern, hazel, heather, heron, ivy, kingfisher, lark, mistletoe, nectar, newt, otter, pasture and willow. The words taking their places in the new edition included attachment, block-graph, blog, broadband, bullet-point, celebrity, chatroom, committee, cut-and-paste, MP3 player and voice-mail … For blackberry, read Blackberry".

On the contrary, detailed observation of nature in Gaelic culture is demonstrated in words listed in Some Lewis Moorland Terms: A Peat Glossary [3]. Two of my favourites include: 'rionnach maoim' or 'the shadows cast on the moorland by clouds moving across the sky on a bright and windy day'; and 'èit' or 'the practice of placing quartz stones in streams so that they sparkle in moonlight and thereby attract salmon to them in the late summer and autumn'.

As Dr MacFarlane succinctly says, “Language deficit leads to attention deficit”. Indigenous language extinction is also leading to loss of ecological knowledge.

Growing scientific research now shows a strong link between time spent in nature and reduced depression, including lower activity in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, which is active during thoughts focused on negative emotion. It has been found that time in nature lowers levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

In an article published in January 2020 by The Yale School of the Environment [4], author Jim Robbins discusses how nature is necessary for physical health and cognitive functioning. Citing a study by The European Centre for Environment and Human Health at the University of Exeter, Jim Robbins draws attention to research which finds that nature has a robust effect on people’s mental, emotional and physical health. Psychiatric unit researchers also found that being in nature reduces feelings of isolation, promotes calm, and lifts mood. Conversely, Nature Deficit Disorder [5] is measured in diminished use of the senses, attention difficulties and higher rates of physical and emotional illnesses [6].

In an article published in January 2020 by The Yale School of the Environment [4], author Jim Robbins discusses how nature is necessary for physical health and cognitive functioning. Citing a study by The European Centre for Environment and Human Health at the University of Exeter, Jim Robbins draws attention to research which finds that nature has a robust effect on people’s mental, emotional and physical health. Psychiatric unit researchers also found that being in nature reduces feelings of isolation, promotes calm, and lifts mood. Conversely, Nature Deficit Disorder [5] is measured in diminished use of the senses, attention difficulties and higher rates of physical and emotional illnesses [6].

Research carried out by the University of Ghent and the Flamine Marine Institute [7] has found that seawater in the air interacts with human genes to slow development of lung cancer and cholesterol. Another survey of 26,000 respondents by the University of Exeter in 2019 [8] reveals mental health benefits of seaside living.

Prescribing nature

Nature is now an officially prescribed medication in some parts of the world. For example, in Shetland an innovative, official NHS GP’s prescription can be, “to stand in the Atlantic wind with eyes closed for 10 minutes” [9]. Wellbeing in the outdoors seems to be independent of exercise.

With this in mind, I created my first lockdown exhibition, Locked Up and Laughing. The exhibition was presented at Gladstone Regional Art Gallery and Museum in Australia. To accompany the exhibition there was (and is) an interactive Facebook group encouraging people to upload their own photos of time spent in nature. We’d still love you to add to the group!

Developing on the themes of Locked Up and Laughing and Rionnach Maoim, I have made two short films. Muigh san Aonach: Out in the Mountains [10] and A’ Chailleach [11].

These works explore the traditional stories of The Cailleach: goddess of the weather, creator of Scotland and maker of mountains. The Cailleach represents the balance in Gaelic culture, between the needs of the wilds and the needs of people. Specifically, in her role as Weather Goddess, the project questions how respect for traditional knowledge and engagement with wilderness, can inform action to the climate crisis being addressed by COP26.

To protect and personally benefit from wilderness we need to know it, as did the Gaels.

Dìle bhàite - A heavy downpour

Sgùrachadh - Misty rain

Steallan uisge - Spatters of rain

Ceòban - Misty drizzling rain

Dòrtadh - Pouring rain

Plom - A spot of rain

Marcach sìne - Driving sheets of rain

On a hill that is...

Meall Garbh - Bare, round, lumpy and rough

Aonach Eagach - A notched high ridge

Cnoc Gaothach - Small, rounded and windy

Coire an t-Sneachda - A snowy glacial hollow

Càrn na Còinnich - Stony and mossy

Caisteal Corrach - A lofty castle

Sìthean Mòr - A great fairy knoll

A' Chailleach - Like a stooped old woman, Queen of the weather, Goddess who created Scotland [12].

- To read more, visit judithparrott.com

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Created for The Colmcille Legacy Award, a national arts and heritage award scheme created in partnership with Bòrd na Gàidhlig to commemorate the life and cultural legacy of Colmcille throughout the Year of Colmcille,1500.

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/27/robert-macfarlane-word-hoard-rewilding-landscape

[3] Compiled by Anne Campbell in collaboration with Finlay MacLeod, Donald Morrison and Catriona Campbell. Published by FARAM in Glasgow, 2013.

[4] https://e360.yale.edu/features/ecopsychology-how-immersion-in-nature-benefits-your-health

[5] Richard Louv, 2005

[6] Nature deficit disorder 'damaging Britain's children' By Richard Black Environment correspondent, BBC News Published 30 March 2012

[7] Scientific journal Scientific Reports, with public access. www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-36866-3

[8] https://www.exeter.ac.uk/news/featurednews/title_754908_en.html

[10] The film was the outcome of a GUIR! residency with Glasgow Life, and was supported by Bòrd na Gàidhlig and Glasgow Life

[11] Created for The Dear Green Bothy, a collaborative cultural programme from the University of Glasgow’s College of Arts showcasing creative and critical responses to climate emergency.

[12] The Cailleach – The woman that created Scotland. All names on this list are hills and mountains of Scotland

Wild and Well

Celebrating the invaluable connection between wild places and people's health